In this blog, Mallika, Data and Research Officer at Nacro, explores the experiences of people being released from prison into homelessness and the efforts underway to address the growing issue.

World Homeless Day aims to raise awareness of the needs of people currently experiencing homelessness and promote support in local communities.

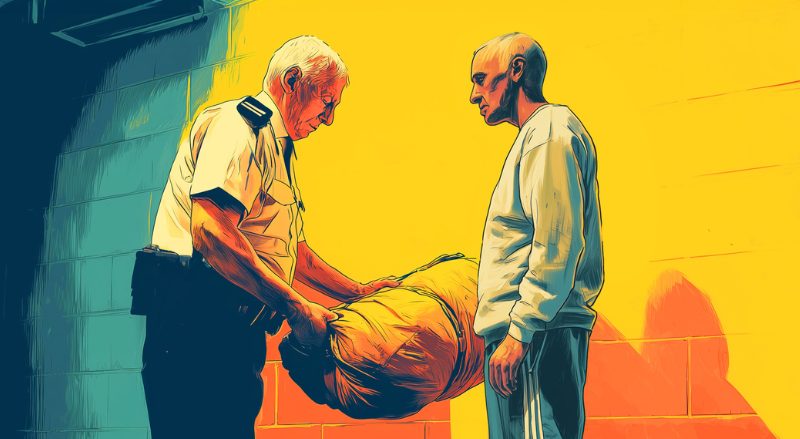

Leaving prison without a home is unfortunately far too common, and every month, around 1,000 people leave prison into homelessness, and evidence shows that this doubles their risk of reoffending.

Although the number of people leaving prison has increased (rising from 70,040 to 86,040) this has been outpaced by the increase in the number leaving homeless (rising from 9,210 to 12,840). This is a 40% rise in the last year.